One pregnancy test down, Emma thinks the gadget is broken. She takes another the next day. Then another. By the fourth one it becomes obvious to her that it wasn’t flawed, and spends the weekend sitting on the floor and staring at the wall.

“What are my parents going to say? Should I tell them? I shouldn’t tell anyone, actually. I’ll just go to the doctor. Is that even allowed? What if the doctor tells someone or judges me?”

In England, she knows terminating a pregnancy is legal, but it isn’t that easy. Everyone knows its something that will be on the back of her mind forever, and she begins to question her own morality. Did she fail society because she was too young to have a baby and knows that she cannot properly care for a child? What does society expect from a woman, anyway? They can’t be perfect. The psychology behind getting an abortion does not make news headlines, instead only what lawmakers and protesters argue. It is a lot more personal than that. Looking at the UK and Australia, terminating a pregnancy seems like a simple and lenient process at the surface, but I argue that a lot of the process depends on continued stigma and attitudes of those directly involved, even years after any procedure takes place. Comparing the two countries, they are similar in that parts of it make it a crime for anyone aiding in terminating a pregnancy and other parts it is justified and legal.

Cockrill et. al. (2017) notes the three types of stigma behind young women deciding on having an abortion or who had one: internalized, felt, and enacted. Literature largely argues that women tend to justify or blame others as an excuse for having the procedure, or even fall into secretive behaviors because of condemnation and negative attitudes around the world.

Elective abortion is still seen by many as a “deviant” behavior, so laws depend on the attitudes of legislators. Rosen and Martindale 91975) analyzed the acceptance of “traditional norms of sexual behavior,” based on the idea that women who generally fall under the stereotype of the women’s role tend to get abortions. The findings back in 1975 predicted change in the feminist movement and push for changing societal norms. We see this happening in our own country and a lot in the Western world in general, so justifying an abortion seems to be a lot more accepted, however complying with the law can be difficult, and what is even harder is for a woman to deal with the stigma herself, especially when society convinces someone to shape their own thoughts about themselves.

In England, Hogart (2017) analyzed narratives of young women to study stigmatization around having abortions. Their resistance to views on deviant behavior varied depending on their socio-economic situations, personal relationships, how they became pregnant, and their own values. Internalized stigma was seen as harder to deal with than struggling with societal norms, seeing that norms were more likely to be challenged than when women internalize the negativity or cannot morally justify the procedure themselves. This is notable because the right to an abortion in the UK was passed in 1967, where legal termination depends on the following:

- That the pregnancy has not exceeded 24 weeks

- The continuation of the pregnancy would involve risk to the life

- There is a substantial risk that if the child is born they would suffer mental or physical abnormalities

- That the abortion is necessary to prevent permanent injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman

Therefore, the “ok” to proceed with an abortion can largely depend on the discretion of the doctor. They need to determine whether the pregnant woman is in a position that will lead her to damaged mental health if they continue with the pregnancy. The way that law is written in the UK largely creates a perception that abortion is a “near-criminal” act. In Northern Ireland, abortion is prohibited completely, but women are allowed to travel to have the procedure done. External views on what is simply a “medical procedure” can affect the mental health and self-perception of a woman and her family.

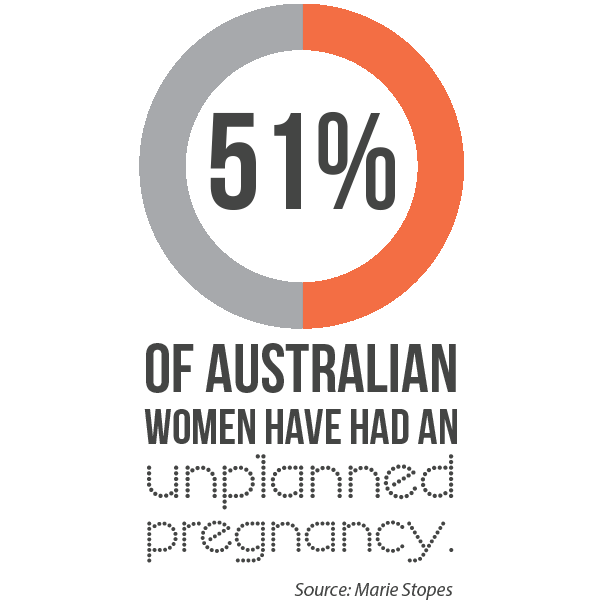

Looking at Australia, many would expect similar policies since they tend to see the two countries in the same light. Norris et al. (2011) claim that “[a]bortion stigma is affected by both by legislative initiatives that establish fetal personhood and gestational age limits and by discourses that influence cultural values.” This is despite the large numbers in abortions that Australian women have each year. The commonality does not account for the negativity that women feel about themselves. Most of the Australian states have similar policies, giving discretion to the doctor that the woman in question would face severe mental or physical damage if they continue with pregnancy, but how much is that decision based on the wording of the law or historical view of abortion as deviance? Further research should focus on qualitative analysis on the doctors themselves who might face scrutiny. Regardless, abortion in Australia is complicated. Two states, Queensland and New South Wales, continue to have laws in place where abortion is a crime. The rest follow the template of doctor’s approval and legal before the 20-24-week period (Willis 2018) However, access to these clinics is limited or nearly impossible in a lot of the country. This could be due to a lot of reasons but looking back at the way abortion is framed as societal deviance in the political discourse. It is available to women but remains in criminal codes (Ryan, 2014). How does this affect the doctors’ decisions? Even when they do go on with the procedure, women still keep it a secret.

For more on Australia, visit: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp9899/99rp01 (it is more extensive than I can summarize)

As a whole, both the UK and Australia follow a template that allows women to get an elective abortion. The fight for these rights involves justifying and countering the stigma and view of killing an unborn child as a deviant behavior, and the way it is written in law make it even harder for it to be accepted and seen as simply a medical procedure without tons of external implications. This hurts the mental health of a lot of people, not only the pregnant woman, but their families. Studies that I looked at in this report show that stigma can be looked at in different ways and obviously affect how women see themselves and make decisions, even though the legality of the medical procedure lets them decide, for the most part. The amount of people keeping it a secret might be the biggest red flag that it is far behind being accepted, even in the countries that are usually seen as free and with forward-thinking populations. If I had a solution, I would propose it. But when it comes down to how someone sees themselves, the roots of the problem are harder to define.

Work Cited

Boyle, MichaelP. 1, mboyle@wcupa. edu, & Armstrong, CoryL. 2. (2009). Measuring Level of Deviance: Considering the Distinct Influence of Goals and Tactics on News Treatment of Abortion Protests. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 17(4), 166–183. Retrieved from hus.

Cockrill K and Nack A, “I’m not that type of person…”: managing the stigma of having an abortion, Deviant Behavior, 2013 (forthcoming).

Cockrill, K., Upadhyay, U. D., Turan, J., & Greene Foster, D. (2013). The stigma of having an abortion: development of a scale and characteristics of women experiencing abortion stigma. Perspectives On Sexual And Reproductive Health, 45(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1363/4507913

Hoggart, L. (2017). Internalised abortion stigma: Young women’s strategies of resistance and rejection. Feminism & Psychology, 27(2), 186–202. Retrieved from a9h.

Norris, A., Bessett, D., Steinberg, J. R., Kavanaugh, M. L., De Zordo, S., & Becker, D. (2011). Abortion stigma: A reconceptualization of constituents, causes, and consequences. Women’s Health Issues, 21(3 Suppl.), S49–S54.

Rosen, R. A. H., & Martindale, L. J. (1975). Abortion as “Deviance”; Traditional Female Roles Vs. The Feminist Perspective. Retrieved from https://libproxy.albany.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=ED123517&site=eds-live&scope=site

Ryan, R. (2014). Bearing responsibility: Reconceiving RU486 and the regulation of women’s reproductive decisions. (Retrieved on December 15, 2015 from) http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au//bitstream/2123/11474/1/ryan. r_thesis_2014.pdf.

Saraiya, S. (2018). Conceiving Criminality: An Evaluation of Abortion Decriminalization Reform in New York and Great Britain. Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, (Issue 1), 174. Retrieved from edshol.

The Abortion Act of 1967, U.K.

Willis, O. (2018). Is abortion legal in Australia? It’s complicated. ABC health and wellbeing. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/health/2018-05-26/is-abortion-legal-in-australia/9795188