As his parents continue to struggle, Ralph does not understand the situation that he is being placed in. Ralph thinks that it is his fault but is too young to understand what is actually happening. The moments where Ralph’s father continues to leave the house are kept hidden and forces him to feel unsafe. As depression kicks in, Ralph does not know what to do.

“Do I really have to leave my family? What is going on? I might need serious help. I hope there is someone out there who will tell me what is going on with my family and will actually care for my well being”.

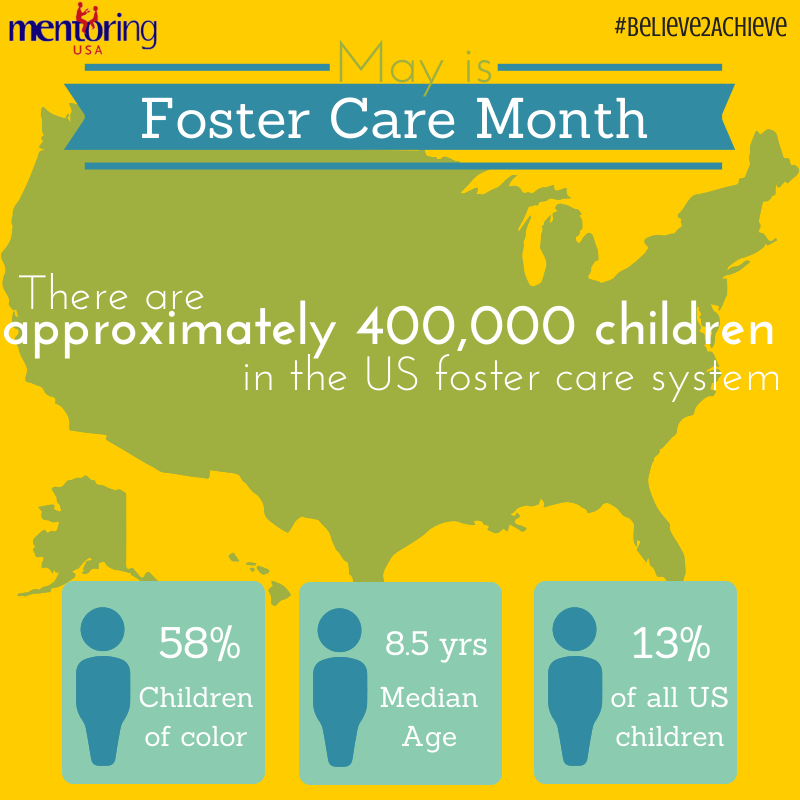

Foster care sounds like a child’s worse nightmare, but the living situation at home could damage a child’s psychology for the rest of their lives. There are growing numbers of children in foster care all over North America, for many reasons, most of which are not the fault of the child, or even of the parents. The rise in substance abuse correlates with the need to take the children out of the home, and quality of life for youth takes a toll. Of course, every state and demographic differ in why these numbers are rising, but there is good indication that the way countries’ governments perceive the children’s well-being creates the foster care environment. I argue that Canada’s approach to foster care may be counterproductive, and statistics in drug abuse and academic performance could be indicators of lower standards than in the U.S.

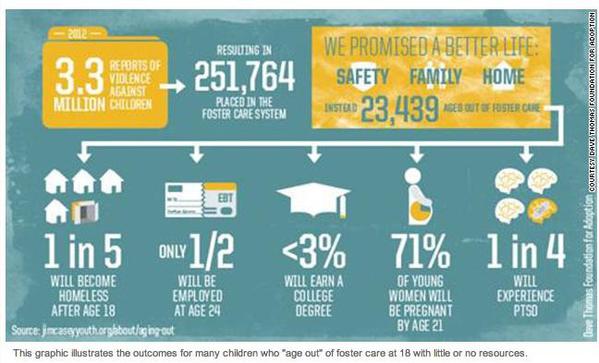

In the United States, the Department of Health and Human Services continuously address the rise in numbers that are being calculated at the end of each fiscal year since 2015. The Acting Assistant Secretary for Children and Families issued a statement saying:

“The continued trend of parental substance abuse is very concerning, especially when it means children must enter foster care as a result. The seriousness of parental substance abuse, including the abuse of opioids, is an issue we at HHS will be addressing through prevention, treatment and recovery-support measures.”

Clearly, the issue is more complex than the conditions that children face in foster care, and while the goal is to improve their childhood well-being away from home, the primary policy goal is to prevent a child from having to enter foster care in the first place. Keeping a child at home and improving families is a better approach, in some cases, than opting for a complete change of living for a kid.

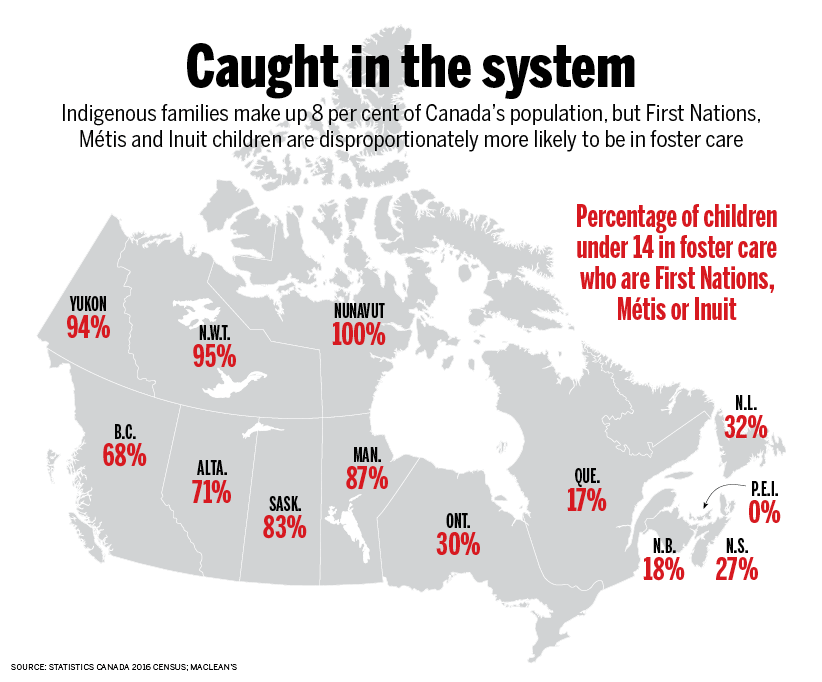

As Canada is in the highest percentile in terms of quality of life in the world, its worth looking at the micro-level: the children’s’ developmental environment. According to the University of Texas, children are also seeing rising numbers in foster care, but differ in their system and policies. For Canada, they base the decision to pull a child from their home on a “child safety” approach that immediately takes the child out of the home if they feel that they are in danger. A better situation is not always promised when there is an overflow of capacity.

Case studies conducted by Boyd et. al. (2016) find that “the role of state interventions in perpetuating the marginalization that occurs [in] young people’s lives… increase their vulnerability to police and criminal justice encounters.” Particularly in Canada (Vancouver), policies stripping children away from their parents without the resources to provide improved care can be counterproductive, leading young people to illicit drug use and homelessness. Although this is also likely to happen in broken homes, the shock of pulling kids out of their families instead of providing counseling might be a bigger problem in the country (Barron, n.d.). The lack of data keeping track of those in the foster care system makes this even harder to analyze compared to the U.S. However, the Huffington post states that data still shows Canada “ha[ving] one of the highest rates of kids in care in the world,” going on to acknowledge how news headlines are reporting a crisis where some children have even died while receiving service (2015). What does this mean for the future working-class generation?

Part of the assessment can be linked to patterns of youth deviance such as drug use, academic performance, and relationships. Statistically in Canada, 60% of illicit drug users in Canada are between 15 and 24 (Canadian Centre for Addictions, 2015). Although drug use is highest among people in their late teens and twenties in the U.S., it was still kept to “22.6 percent of 18- to 20-year-olds reported using an illicit drug in the past month,” while drug use is actually increasing in those aged 50 to 60s. This highlights the problems at home and who is being affected in the two countries, where it might suggest that the U.S. faces the problem more at the parenting level. To compare levels of academic performance, it is difficult to conclude a correlation between the factors that we’re looking at here, especially since there are more similarities than differences. Both, as a whole, do reasonably well in retaining students and their performance throughout primary, secondary, and tertiary education.

Without a full-fledged statistical analysis, it seems that Canada and the U.S. face distinct problems in their policies and how they approach children from broken families. Many more indicators can be analyzed in assessing performance of installed programs, but the countries have different demographics. As usual, the issue is more complex than cause-and-effect, but with that being said, rising numbers and lack of resources in Canada calls for revisiting their policies on foster care.

Resources

Barron, J. (n.d.) How do we compare? Looking at foster care systems around the world. University of Texas at Austin, Texas Institute for Child & Family Wellbeing. Retrieved from https://txicfw.socialwork.utexas.edu/how-do-we-compare-looking-at-foster-care-systems-around-the-world/

Barron, J. (n.d.) How do we compare? Looking at foster care systems around the world. University of Texas at Austin, Texas Institute for Child & Family Wellbeing. Retrieved from https://txicfw.socialwork.utexas.edu/how-do-we-compare-looking-at-foster-care-systems-around-the-world/ 16465722e362

Boyd, J., Fast, D., & Small, W. (2016). Pathways to criminalization for street-involved youth who use illicit substances. Critical Public Health, 26(5), 530-541. doi:http://dx.doi.org.libproxy.albany.edu/10.1080/09581596.2015.1110564

Brownell, M. and McMurtry, N. (2015) Why does Canada have so many kids in foster care? The Huffington Post. Retrieved from https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/marni-brownell/foster-care-in-canada_b_8491318.html

Canadian Centre for Addictions (2015). Teen drug abuse facts and their implications. Retrieved from https://canadiancentreforaddictions.org/teen-drug-abuse-facts/

Department of health and human services. (2017). Number of children in foster care continues to increase. Report retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/media/press/2017/number-of-children-in-foster-care-continues-to-increase

National Institute on Drug Abuse (2015). Nationwide Trends. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/nationwide-trends